Weierstrass's elliptic functions

In mathematics, Weierstrass's elliptic functions are elliptic functions that take a particularly simple form; they are named for Karl Weierstrass. This class of functions are also referred to as p-functions and generally written using the symbol ℘ (or  ) (a stylised letter p called Weierstrass p).

) (a stylised letter p called Weierstrass p).

Symbol for Weierstrass P function

Contents |

Definitions

Weierstrass P function defined over a subset of the complex plane using a standard visualization technique in which white corresponds to a pole, black to a zero, and maximal saturation to  Note the regular lattice of poles, and two interleaving lattices of zeros.

Note the regular lattice of poles, and two interleaving lattices of zeros.

The Weierstrass elliptic function can be defined in three closely related ways, each of which possesses certain advantages. One is as a function of a complex variable z and a lattice Λ in the complex plane. Another is in terms of z and two complex numbers ω1 and ω2 defining a pair of generators, or periods, for the lattice. The third is in terms z and of a modulus τ in the upper half-plane. This is related to the previous definition by τ = ω2/ω1, which by the conventional choice on the pair of periods is in the upper half-plane. Using this approach, for fixed z the Weierstrass functions become modular functions of τ.

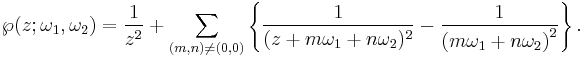

In terms of the two periods, Weierstrass's elliptic function is an elliptic function with periods ω1 and ω2 defined as

Then  are the points of the period lattice, so that

are the points of the period lattice, so that

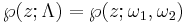

for any pair of generators of the lattice defines the Weierstrass function as a function of a complex variable and a lattice.

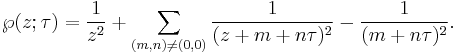

If  is a complex number in the upper half-plane, then

is a complex number in the upper half-plane, then

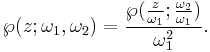

The above sum is homogeneous of degree minus two, from which we may define the Weierstrass ℘ function for any pair of periods, as

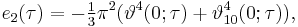

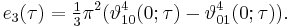

We may compute ℘ very rapidly in terms of theta functions; because these converge so quickly, this is a more expeditious way of computing ℘ than the series we used to define it. The formula here is

There is a second-order pole at each point of the period lattice (including the origin). With these definitions,  is an even function and its derivative with respect to z, ℘′, an odd function.

is an even function and its derivative with respect to z, ℘′, an odd function.

Further development of the theory of elliptic functions shows that the condition on Weierstrass's function (correctly called pe) is determined up to addition of a constant and multiplication by a non-zero constant by the condition on the poles alone, amongst all meromorphic functions with the given period lattice.

Invariants

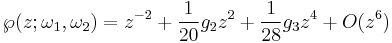

If points close to the origin are considered the appropriate Laurent series is

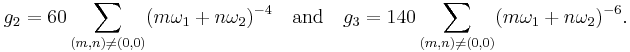

where

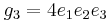

The numbers g2 and g3 are known as the invariants—they are two terms out of the Eisenstein series.

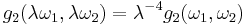

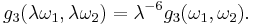

Note that g2 and g3 are homogeneous functions of degree −4 and −6; that is,

and

Thus, by convention, one frequently writes  and

and  in terms of the half-period ratio

in terms of the half-period ratio  and take

and take  to lie in the upper half-plane. Thus,

to lie in the upper half-plane. Thus,  and

and  .

.

The Fourier series for  and

and  can be written in terms of the square of the nome

can be written in terms of the square of the nome  as

as

and

where  is the divisor function. This formula may be rewritten in terms of Lambert series.

is the divisor function. This formula may be rewritten in terms of Lambert series.

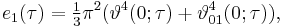

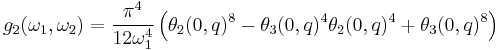

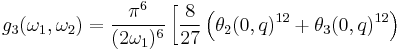

The invariants may be expressed in terms of Jacobi's theta functions. This method is very convenient for numerical calculation: the theta functions converge very quickly. In the notation of Abramowitz and Stegun, but denoting the primitive half-periods by  , the invariants satisfy

, the invariants satisfy

and

where  is the half-period ratio and

is the half-period ratio and  is the nome.

is the nome.

Special cases

If the invariants are g2 = 0, g3 = 1, then this is known as the equianharmonic case; g2 = 1, g3 = 0 is the lemniscatic case.

Differential equation

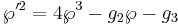

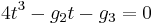

With this notation, the ℘ function satisfies the following differential equation:

where dependence on  and

and  is suppressed.

is suppressed.

This relation can be quickly verified by comparing the poles of both sides, for example, the pole at z = 0 of lhs is

while the pole at z = 0 of

Comparing these two yields the relation above.

Integral equation

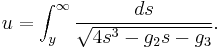

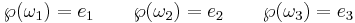

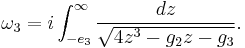

The Weierstrass elliptic function can be given as the inverse of an elliptic integral. Let

Here, g2 and g3 are taken as constants. Then one has

The above follows directly by integrating the differential equation.

Modular discriminant

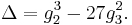

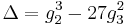

The modular discriminant Δ is defined as

This is studied in its own right, as a cusp form, in modular form theory (that is, as a function of the period lattice).

Note that  where

where  is the Dedekind eta function.

is the Dedekind eta function.

The presence of 24 can be understood by connection with other occurrences, as in the eta function and the Leech lattice.

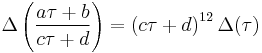

The discriminant is a modular form of weight 12. That is, under the action of the modular group, it transforms as

with τ being the half-period ratio, and a,b,c and d being integers, with ad − bc = 1.

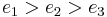

The constants e1, e2 and e3

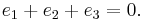

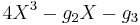

Consider the cubic polynomial equation  with roots

with roots  ,

,  , and

, and  . If the discriminant

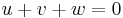

. If the discriminant  is not zero, no two of these roots are equal. Since the quadratic term of this cubic polynomial is zero, the roots are related by the equation

is not zero, no two of these roots are equal. Since the quadratic term of this cubic polynomial is zero, the roots are related by the equation

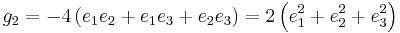

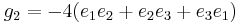

The linear and constant coefficients (g2 and g3, respectively) are related to the roots by the equations[1]

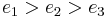

In the case of real invariants, the sign of  determines the nature of the roots. If

determines the nature of the roots. If  , all three are real and it is conventional to name them so that

, all three are real and it is conventional to name them so that  . If

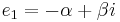

. If  , it is conventional to write

, it is conventional to write  (where

(where  ,

,  ), whence

), whence  and

and  is real and non-negative.

is real and non-negative.

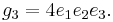

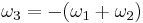

The half-periods ω1 and ω2 of Weierstrass' elliptic function are related to the roots

where  . Since the derivative of Weierstrass' elliptic function equals the above cubic polynomial of the function's value,

. Since the derivative of Weierstrass' elliptic function equals the above cubic polynomial of the function's value,  for

for  ; if the function's value equals a root of the polynomial, the derivative is zero.

; if the function's value equals a root of the polynomial, the derivative is zero.

If  and

and  are real and

are real and  , the

, the  are all real, and

are all real, and  is real on the perimeter of the rectangle with corners

is real on the perimeter of the rectangle with corners  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . If the roots are ordered as above (

. If the roots are ordered as above ( ), then the first half-period is completely real

), then the first half-period is completely real

whereas the third half-period is completely imaginary

Addition theorems

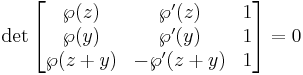

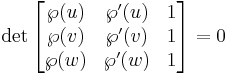

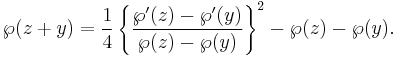

The Weierstrass elliptic functions have several properties that may be proved:

(a symmetrical version would be

where  ).

).

Also

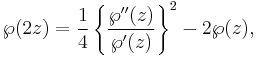

and the duplication formula

unless  is a period.

is a period.

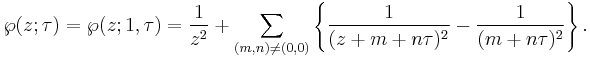

The case with 1 a basic half-period

If  , much of the above theory becomes simpler; it is then conventional to write

, much of the above theory becomes simpler; it is then conventional to write  for

for  . For a fixed τ in the upper half-plane, so that the imaginary part of τ is positive, we define the Weierstrass ℘ function by

. For a fixed τ in the upper half-plane, so that the imaginary part of τ is positive, we define the Weierstrass ℘ function by

The sum extends over the lattice {n+mτ : n and m in Z} with the origin omitted. Here we regard τ as fixed and ℘ as a function of z; fixing z and letting τ vary leads into the area of elliptic modular functions.

General theory

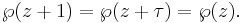

℘ is a meromorphic function in the complex plane with a double pole at each lattice points. It is doubly periodic with periods 1 and τ; this means that ℘ satisfies

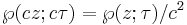

The above sum is homogeneous of degree minus two, and if c is any non-zero complex number,

from which we may define the Weierstrass ℘ function for any pair of periods. We also may take the derivative (of course, with respect to z) and obtain a function algebraically related to ℘ by

where  and

and  depend only on τ, being modular forms. The equation

depend only on τ, being modular forms. The equation

defines an elliptic curve, and we see that  is a parametrization of that curve.

is a parametrization of that curve.

The totality of meromorphic doubly periodic functions with given periods defines an algebraic function field, associated to that curve. It can be shown that this field is

so that all such functions are rational functions in the Weierstrass function and its derivative.

We can also wrap a single period parallelogram into a torus, or donut-shaped Riemann surface, and regard the elliptic functions associated to a given pair of periods to be functions defined on that Riemann surface.

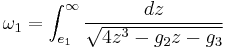

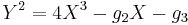

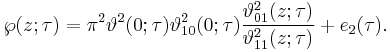

The roots e1, e2, and e3 of the equation  depend on τ and can be expressed in terms of theta functions; we have

depend on τ and can be expressed in terms of theta functions; we have

Since  and

and  we have these in terms of theta functions also.

we have these in terms of theta functions also.

We may also express ℘ in terms of theta functions; because these converge very rapidly, this is a more expeditious way of computing ℘ than the series we used to define it.

The function ℘ has two zeros (modulo periods) and the function ℘′ has three. The zeros of ℘′ are easy to find: since ℘′ is an odd function they must be at the half-period points. On the other hand it is very difficult to express the zeros of ℘ by closed formula, except for special values of the modulus (e.g. when the period lattice is the Gaussian integers). An expression was found, by Zagier and Eichler.[2]

The Weierstrass theory also includes the Weierstrass zeta function, which is an indefinite integral of ℘ and not doubly periodic, and a theta function called the Weierstrass sigma function, of which his zeta-function is the log-derivative. The sigma-function has zeros at all the period points (only), and can be expressed in terms of Jacobi's functions. This gives one way to convert between Weierstrass and Jacobi notations.

The Weierstrass sigma-function is an entire function; it played the role of 'typical' function in a theory of random entire functions of J. E. Littlewood.

Relation to Jacobi elliptic functions

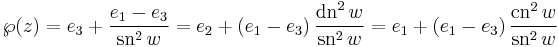

For numerical work, it is often convenient to calculate the Weierstrass elliptic function in terms of the Jacobi's elliptic functions. The basic relations are[3]

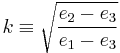

where e1-3 are the three roots described above and where the modulus k of the Jacobi functions equals

and their argument w equals

Notes

References

- Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene A., eds. (1965), "Chapter 18", Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables, New York: Dover, pp. 627, ISBN 978-0486612720, MR0167642, http://www.math.sfu.ca/~cbm/aands/page_627.htm.

- N. I. Akhiezer, Elements of the Theory of Elliptic Functions, (1970) Moscow, translated into English as AMS Translations of Mathematical Monographs Volume 79 (1990) AMS, Rhode Island ISBN 0-8218-4532-2

- Tom M. Apostol, Modular Functions and Dirichlet Series in Number Theory, Second Edition (1990), Springer, New York ISBN 0-387-97127-0 (See chapter 1.)

- K. Chandrasekharan, Elliptic functions (1980), Springer-Verlag ISBN 0-387-15295-4

- Konrad Knopp, Funktionentheorie II (1947), Dover; Republished in English translation as Theory of Functions (1996), Dover ISBN 0-486-69219-1

- Serge Lang, Elliptic Functions (1973), Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-04162-6

- Reinhardt, William P.; Walker, Peter L. (2010), "Weierstrass Elliptic and Modular Functions", in Olver, Frank W. J.; Lozier, Daniel M.; Boisvert, Ronald F. et al., NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521192255, MR2723248, http://dlmf.nist.gov/23

- E. T. Whittaker and G. N. Watson, A course of modern analysis, Cambridge University Press, 1952, chapters 20 and 21

![\wp(z; \tau) = \pi^2 \vartheta^2(0;\tau) \vartheta_{10}^2(0;\tau){\vartheta_{01}^2(z;\tau) \over \vartheta_{11}^2(z;\tau)}-{\pi^2 \over {3}}\left[\vartheta^4(0;\tau) %2B \vartheta_{10}^4(0;\tau)\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/4e21b89d0e9918d8f063825e99633a5a.png)

![g_2(\tau)=\frac{4\pi^4}{3} \left[ 1%2B 240\sum_{k=1}^\infty \sigma_3(k) q^{2k} \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/9eb3bade5911b287a848ec1be7327ace.png)

![g_3(\tau)=\frac{8\pi^6}{27} \left[ 1- 504\sum_{k=1}^\infty \sigma_5(k) q^{2k} \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d5ecc4215cb5f19b341409b8d949c115.png)

![\left. {} -

\frac{4}{9}\left(\theta_2(0,q)^4%2B\theta_3(0,q)^4\right)\cdot

\theta_2(0,q)^4\theta_3(0,q)^4

\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a5112bcdf597eb5ff23a7d3d563bcbc7.png)

![[\wp'(z)]^2 = 4[\wp(z)]^3-g_2\wp(z)-g_3, \,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/324d789aeb0da56cb62ec5fadd88ed8b.png)

![[\wp'(z)]^2|_{z=0}\sim \frac{4}{z^6}-\frac{24}{z^2}\sum \frac{1}{(m\omega_1%2Bn\omega_2)^4}-80\sum \frac{1}{(m\omega_1%2Bn\omega_2)^6}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/c0eb805627f418e99ef367e98cae72d0.png)

![[\wp(z)]^3|_{z=0}\sim \frac{1}{z^6}%2B\frac{9}{z^2}\sum \frac{1}{(m\omega_1%2Bn\omega_2)^4}%2B15\sum \frac{1}{(m\omega_1%2Bn\omega_2)^6}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e119f2c026ac9afc19c0bc5cc8e53a11.png)